Although The Elcho is the oldest and most prestigious long range rifle contest in the world, its origins and the History of The Elcho Shield are less well-known.

Volunteer Force and The National Rifle Association

The Volunteer Force was formed in 1859 in response to the fear of a French invasion. It started in a small way with informal groups and rifle clubs, but such was the enthusiasm that the government authorised the Lord Lieutenants of each county to organise local Corps. Thousands flocked to join – partly because, as there were no drill sergeants, the main concern was rifle shooting and people were keen to participate in this new sport. There were virtually no rules about danger areas, and it was easy to find suitable sites for target practice.

In the late summer of 1859, leaders of the Volunteer movement attended the Hythe School of Musketry, and while there, resolved to further the aims of the Volunteer Movement and rifle shooting by forming a national association. This would be for “the encouragement of Volunteer Rifle Corps and the promotion of rifle shooting throughout Great Britain.” Their ideas accorded with those of the London Rifle Brigade and a successful joint meeting, with the object of forming a National Rifle Association, was held in November. Then Lord Elcho, an enthusiastic protagonist of the scheme and a keen Volunteer, wrote to the Times on 9 December, setting out the aims of the new Association and the plans to hold a great annual National Meeting for rifle shooting. The first of these would be in July 1860.

The match for the Elcho Shield – arose from a challenge by Scotland to England in 1861. The terms of the challenge pleased Lord Elcho, who had determined to give a prize to the National Rifle Association’s annual meeting at Wimbledon. He wished it to be a prize “for annual competition as an encouragement to International Small-bore* shooting, and also that my name might be perpetuated in connection with the Association and the volunteers, and thus it will be long after I left this sublunary scene, when otherwise all personal remembrance of ones work would be forgotten”.

* Match-rifle was called small-bore in the early days.

Design of The Elcho Shield

Lord Elcho asked his friend George Frederick Watts the well-known artist to design a suitable trophy, and the iron shield (6ft x 3ft) is a triumph of mid-Victorian art. Watts was a well-known and popular artist who had painted many fine portraits, but was perhaps better known for his sickly allegorical and historical scenes. He showed frequently at the Royal Academy, and was seldom without a sketch book in his hand, while his sculpture of a huge horse and rider gave him the nickname of “England’s Michelangelo”.

Watts decided that the trophy would be an iron shield six feet high, and Lord Elcho wrote to him on 14 January 1860 saying “I wish to leave the conception as well as the drawing of our shield entirely to yourself”. Watts drew the figures and scenes for subjects suggested by Lord Elcho, as well as Britannia, and the medallion head of Victoria. It is not known whether he was responsible for the detailed decoration. The shape of the Shield was designed by the son of a Mr Cayley, who was MP for the North Riding of Yorkshire from 1832 to 1862. The model for the Englishman at the base of the Shield was a young man called Reginald Cholmondeley, an amateur artist and assistant to Watts. The model for the Scotsman is unknown. The project was entrusted to Elkington and Co, who employed a Frenchman or Belgian by the name of Mainfroid to do the work. The shield was to be executed in repousse – the design being pushed out from the back – while the bands delineating the different areas of the burnished shield were to be gilded.

Britannia presides over scenes of contests between England and Scotland, though at the base a Scotsman and an Englishman shake hands. Roses and thistles (plus a spider) garland the edge, and a portrait head of Queen Victoria takes a central place. Originally brightly burnished, and decorated with gold bands it must have been magnificent. Sadly, it is now a dull grey, for all the gilt has gone, and the surface is no longer burnished.

The Challenge

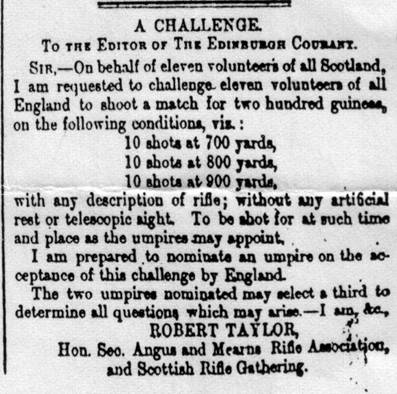

But though its design seems to have been well underway by the spring of 1860 there was no suitable contest for which it could be awarded. Then in August 1861 – after the second Wimbledon Meeting – and on the eve of the second great rifle meeting in Montrose, the following letter appeared in the Montrose and Brechin Review, on 2 August 1861 and in the Edinburgh Courant on 30 July 1861:-

Robert Taylor ran large and successful rifle meetings on the links of Montrose, which were combined with Highland Games, side-shows, floral arches and flags, open hours for the public houses, cricket and golf matches, a military review, civic balls, banquets and receptions to create a gala week for between 30 – 50,000 people with special trains arriving from as far away as Edinburgh and Glasgow. He must have been a well-known local figure, but so far nothing has been discovered of the eleven challengers whom he represented. Were any of the Rosses – keen exponents of long range shooting, or, indeed, Lord Elcho himself involved?

We do not know how much notice was taken of the challenge at the 1861 Montrose meeting, but certainly nothing seems to have happened until it was brought to the notice of the Editor of the Volunteer Service Gazette. He wrote on 7 September deprecating that the challenge had not been sent to him in the first place rather than to “some provincial papers”, but otherwise he took up the idea with enthusiasm, and hoped there would be a match that year. Within a few weeks Lord Bury (England) and Captain Horatio Ross (Scotland) had been appointe Captains, and it was only accepted with reluctance that it would take a little time to agree the conditions and rules. These were completed by December 1861. The match was now to be an annual event, at 800, 900, and 1000 yards, while the question of a large money prize was dropped. The first contest would be at the Wimbledon Meeting of 1862.

Lord Bury was the thirty-year-old son of the Earl of Albemerle, and treasurer of the Royal Household. He was a fine shot who had tied for the Queen’s Prize with Private Jopling in 1861. Horatio Ross was sixty-one, and the Grand Old Man of Scottish shooting. He was a superlative sporting shot, possibly only surpassed in his lifetime as a deer-stalker by his son Edward. He had a 1400 yards range on his estate at Netherley in Kincardineshire, and had shot with great success at distances up to 1800 yards using targets on boats moored in the Montrose basin. Horatio Ross had initially discouraged the idea of the match, as he felt that it would be difficult or impossible to find eleven worthy Scottish representatives. The final number agreed upon was, of course, eight.

Lord Elcho, when he heard of the proposed match, promptly offered the Shield as a prize. It would appear that though designed in outline, work on the shield had not yet begun, and this was going to take two or three years to complete. In the first rules, the names of the winners each year were to be engraved on the Shield, but this did not happen and instead the background areas are diaper (diamond) patterns of thistles or roses. The back of the shield, being rough and later leather-lined is quite unsuitable. Perhaps a smooth lining had been envisaged but was not practical. Each member of the winning team was to receive a small silver shield engraved with the names of the winners paid for by the losing side.

The First Elcho Matches

The first match was held on 9 July 1862, and attracted a great deal of interest. The English firers wore the red cross of St George, and the Scots the blue saltire of St Andrew on their arms, a custom still adhered to. Diagrams of the English targets were published in the Volunteer Service Gazette, showing all but the last few shots fired. Lord Bury who had made the top score for England at 800 and 900 yards, began disastrously at 1000 yards with eight misses and a ricochet in his first nine shots. It was found that a piece of lead ha lodged in one of the grooves of the barrel and he was permitted to finish with another rifle. His problems however made no difference to the result: England won by 166 points. In spite of this they had to be content at the prize-giving with a drawing of the design for the Shield “Lady Elcho tendered the drawing very gracefully, but assured the victors that Scotland had failed because it was only a sketch. The Scottish eight were reserving their efforts till the actual shield was made.”

In 1863 with Lord Elcho and four members of the Ross family in the Scottish team, Scotland were again beaten, but had reduced the lead to 83 points. Although a model of the Shield was displayed in the Exhibition tent, the English Eight were only given the small silver individual shields.

By 1864, the match was considered as important as the Boat Race, or the Eton v Harrow match at Lords, and Scotland were the victors by 25 points. Though the Shield was still a plaster model it was substantial enough for the Scots to carry off in triumph. The Eight were also given small shields engraved with team names and scores. Two, those won by Wilken and Maxwell, still exist.

Original Plaster Model

The design of the plaster model is rather different from that of the finished Shield but resembles the drawing published in the Illustrated London News in 1865. The crown is flatter with fewer arches. The Queen’s head is heavier, and in an oval, not a circle. On the model, the wording on the garter is in Roman lettering, while on the finished shield Gothic is used. There are various other minor differences, the most important of which is that Bruce’s spider is missing. The whole is coloured a dark dull grey. It would appear that though Watts had designed the Shield roughly in 1860, the design was not finalised until much later, as so much detail was changed between 1863 (the first model) and 1865 when the Shield was finished.

At the beginning of November 1864, the plaster shield was presented to the Lord Provost of Edinburgh in Parliament Square before a jubilant crowd. It was then hung in Parliament House. If the metal shield had not been finished before the next Wimbledon Meeting, the model would doubtless have gone South to be re-presented. In fact, it was two years later, in the Autumn of 1866 that Horatio Ross wrote to the Faculty of Advocates “offering to present to the Faculty the model of the Elcho Challenge Shield now hanging in the lobby of the Parliament House”. This offer was accepted and they returned thanks to Mr Ross. The model remains there to this day, hanging over a doorway in the Box corridor.

The Iron Elcho Shield

In 1865 the iron Shield was finally finished and ready to be presented to the winners – England. It was a magnificent sight. Burnished till it shone like silver and with the bands delineating the hexagonal area at the top of the shield and the sides, bright with gold. A trophy worthy of the match and Lord Elcho’s wishes. He wrote “I paid them [Elkington] £500 for it, but they said it was worth £1500, and I believe it, as the work was most difficult and laborious, and no finer specimen of modern repousse metal work is to be seen.” This then, is the trophy which is competed for each July, though now it has lost its colour and is a worn shadow of its former glory. In spite of the rule that the Shield “shall be kept in some conspicuous place in the country representing the winning team,” England did nothing after their wins in 1865, 67, or 68. It was not until 20 August 1870, that the Lord Mayor of London received the Shield for the first time.

How then, apart from the inadequate written descriptions of the design, do we know what the Shield originally looked like? It was in 1879, when Lord Elcho left the active command of his regiment – the London Scottish, – that “They asked me what I should like to have as a remembrance of our long and happy connection. They proposed a dirk, but I mildly suggested an electro copy of the Elcho Shield, which I said I had always intended to give myself, intending to place it over the dining-room sideboard at Gosford, where, as they readily adopted my suggestion, said memorial presentation copy of my Shield is now happily located.” Today, the Shield shining behind glass, and in an ornate carved frame, forms the centrepiece of the back of a sideboard some fifteen feet wide and twelve high. This is the third and last copy of the Elcho Shield, and the only one now that resembles what Lord Elcho and GF Watts envisaged.

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful to Lady Wemyss for allowing me to see the Elcho sideboard and to read Lord Elcho’s memoirs. I should also like to thank Ted Molyneux and Dick Ellis of the NRA Museum, the curator of the Watts Gallery, Dr Robin Pizer and William Meldrum, all of whom helped in various ways.

Reproduced with kind permission of Rosemary Meldrum